Here is a question: How could we design places of worship that are shared by different faith groups and/or other secular groups? This is a question relevant to historic places of worship - which is the focus of the Empowering Design Project - but also new religious buildings and spaces. Behind this question lies perhaps a more interesting question: Why should we create new or adapt existing and often historical religious buildings into shared spaces?

These questions have become relevant to an increasingly large number of people, at least in the UK, for ostensibly different reasons, relating to issues of social cohesion and inter-cultural communication, theological reasons, or reasons relating to the preservation of heritage and the efficient use of existing resources and spaces. The questions formed the topic of a debate that was organised by the Baroness Warsi Foundation in collaboration with the Empowering Design Practices project (EDP) on the 25th of November 2016 at Liverpool School of Architecture. Chaired by Lord Alton of Liverpool, the debate included a series of provocations from a panel of speakers that brought a diverse range of experience and insights into the topic:

- Dr. Andrew Crompton, Head of the School of Architecture, University of Liverpool

- Daniel Leon and Matthew Lloyd, two of the architects behind the tri-faith prayer space, the Friday, Saturday, Sunday project

- The Most Revd Malcolm McMahon OP, Archbishop of Liverpool

- Sophia de Sousa, member of the Empowering Design Practices project research team & Chief Executive, The Glass-House Community Led Design.

Public debates can some times be a disconnected assembly of different points of view. This was certainly not the case with this one. It felt to me that the discussion between the speakers and the audience evolved as a passionate, but also intimate conversation in which a large number of people had the chance to talk and share their views.

But let’s see some of the arguments and points that were made.

At first the audience was asked to consider "a windowless, white room with a chair and a mat" and maybe a sign that indicates that this is a room where anyone can pray. How useful and meaningful will this be for people who want to pray? Indeed, a large number of public buildings (such as airport, hospitals or schools) have these ‘multi-faith rooms’ – although no legal obligation is currently in place to require the inclusion of these places within public buildings. Dr. Andrew Crompton, the Head of the School of Architecture at University of Liverpool started the debate with this provocation for the audience but also for architecture more generally: can we create places that are sacred for all, discarding all the symbols and features that carry meaning to different faith groups? Or is this is 'a no-mans land’?

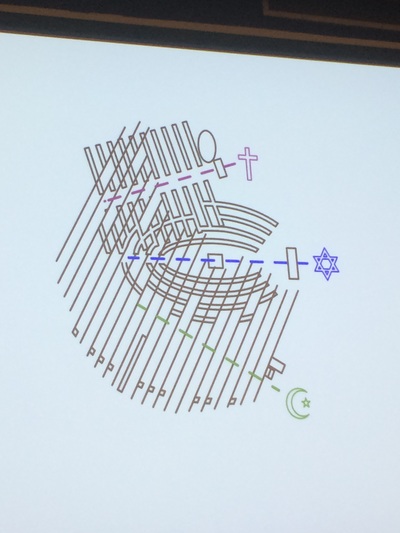

Daniel Leon and Matthew Lloyd, two of the architects behind the tri-faith prayer space, the Friday, Saturday, Sunday project brought a different dimension to the conversation. Their project explores the very question of shared spaces through architecture, experimenting with how the orientation of the spaces will be tackled, how worshipping spaces could be overlaid so as to allow different faiths to witness the practices of each other without compromising their spiritual needs, and how these practices could be wrapped up in a built form able to express meanings relevant to three different faith groups. More recently, they have also started working on the possibility of a more temporal multi-faith structure where some common activities (e.g. cooking) can happen. As Matthew said, “it is difficult to create a meaningful shared space”, but certainly architecture can explore these boundaries.

The final provocation came from Sophia de Sousa, Chief Executive of The Glass-House Community Led Design who represented our EDP project. The provocation started with a series of questions to the audience about the relationship of people with religious buildings which brought to the fore another dimension of the discussion. This is the challenge, not (only) to define the architectural features of a building inhabited by different faith groups, but to understand the meaning that these buildings and places acquire when they accommodate secular activities and wider community uses. In the context of adapting historic places of worship particularly, there are so many different ‘red lines’ for these adaptations depending on the faith group, denomination, but also locality, that the task defies universal design solutions. Ultimately it is the local group that looks after these buildings that determines what is needed and what is meaningful for that particular place.

Some contradictions were also noted during this debate: a member of the audience said, “a lot of people within congregations would know very little about the theological meaning of their buildings”. For them, meaning is embedded in their personal relationship with the building and in some cases the building may be irrelevant to the purpose and identity of a congregation. But it was also argued that for some people the experience of entering into a place of worship is very complex: that it is not only about the perception of archetypical religious features, but it is also about all the sensory information that comes with it (i.e. the distinctive smells and sounds). This sensory environment shapes the important spiritual connections that otherwise can be diluted into nothing.

But again, people and communities also want to ‘build bridges with others’ and shape an identity that is open and inclusive to people from different faiths or cultures. Indeed, tackling social issues or sharing ‘food’ were extensively discussed as common practices that connect people in places of worship. So maybe what this all points to is the need to rethink how we design or adapt places of worship. And understand why or whether different communities (faith or secular) can come together under the same roof. Well, it seems to me the answer is blowing in the wind.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed